In 1996, in preparation for the summer Olympics, Atlanta erected a number of athletic structures to host some of the greatest athletes from around the globe. The Centennial Olympic Stadium would continue to host world-class athletes under the moniker Turner Field, hosting numerous Atlanta Braves postseason appearances in front of almost 50,000 people. However like other olympic stadiums, the challenge to keep the facility maintained and modern was simply too great. This problem isn’t unique to Atlanta by any stretch, and the choice needs to be made: do we funnel more money into an old stadium or build a new one and create a better experience? Not wanting to end up like Montreal (who has dumped millions into maintaining their 1976 Olympic Stadium colossus despite the fact that their host baseball team left the city in 2004 and now only hosts the occasional sporting event), it was decided that a new arena for the Braves would be built to the tune of $672 million.

Cobb County, with a genuine desire to improve its image and quality of life, will be footing the bill for the new stadium and will likely finalize a lease agreement with the team sometime soon. The county, which at 707,000 people has a population slightly larger than the city of Detroit, will add the stadium to a list of growing attractions. That list includes a Six Flags theme park, multiple performing arts centers, The Georgia Ballet, art centers, and a slew of other amusements that you might expect to find in Atlanta and not a neighboring community.

While many new stadium projects have recently come under fire for the sticker shock of development costs, all the buzz coming from Georgia stems from the fact that the new stadium is being built 12 miles outside of the downtown core and across the municipal border into Cobb County. What is unusual here is that this is bucking the recent trend across professional sports of moving out of the suburbs into urban areas.

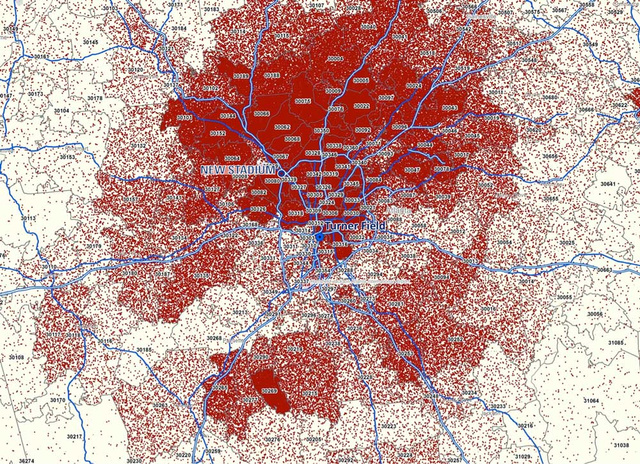

Lots of talk has been flying back and fourth regarding the stadium’s location. This map from Gawker shows that most of the ticket sales for Braves games come from a well-defined region, and that region isn’t anywhere near where Turner Field is located.

We can see from the map above that Turner Field is located right on the edge of where many ticket sales come from, and where the numbers drop off substantially. This map tells, at best, a partial story of why the move came into being.

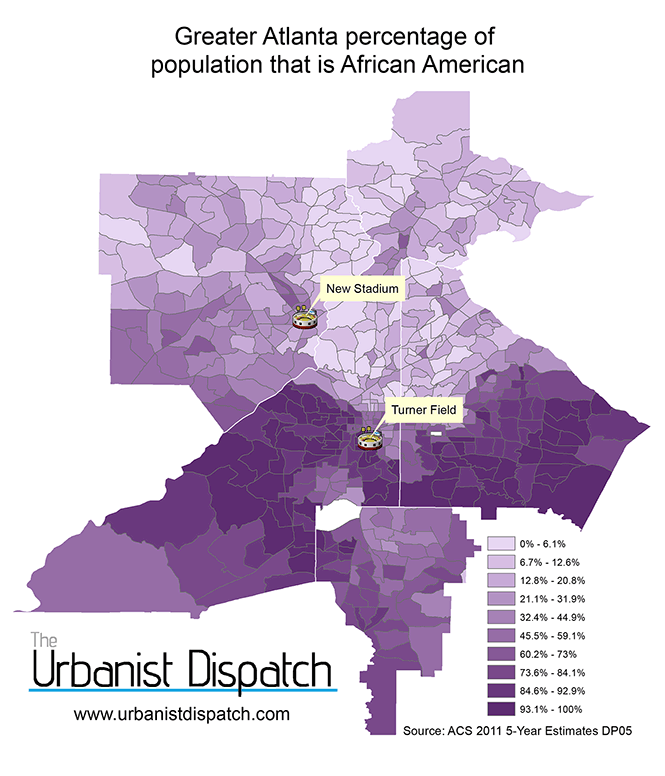

The maps below show white lines separating counties and dark grey lines separating census tracts.

Racial Makeup of Atlanta

There are other maps circulating that show the African American population of the Atlanta area and the new stadium development, suggesting that the team is abandoning their African American supporters by moving out of predominantly African American neighborhoods and favoring white neighborhoods. What is surprising when we break the data down into groups, is that when we try to define what a diverse area looks like, the corner of Cobb County that will house the new stadium looks fairly diverse. While parts of northern Atlanta are predominantly white, Southeast Cobb County has a lot more mid-range shades of purple than light or dark shades. It’s one of the most diverse areas in the Atlanta Metro area. The Atlanta city proper is still very segregated as the map shows, despite the fact that the city is 52% of the city being African American.

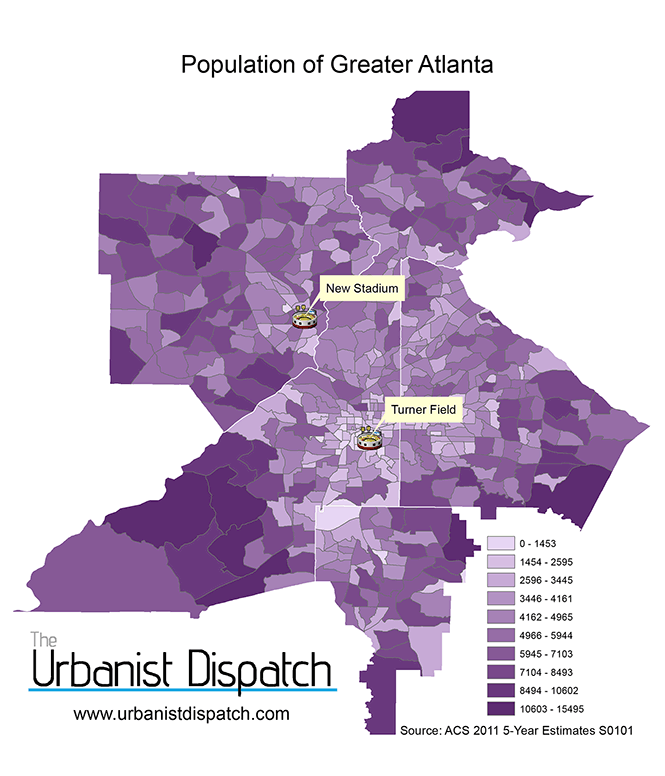

Population of Atlanta

When we look at the overall population, the word that is written across the face of greater Atlanta is Sprawl. The heavily populated census tracts lie in the suburban fringe, not the downtown core (the area around the stadium). Census tracts nationwide average about 4,000 people, however, the degree of variation in Atlanta census tracts is somewhat surprising. While the median is right around 4,000 people, the span lies anywhere from less than 1,500 people to over 15,000 people. The Cobb county areas surrounding the new stadium have more people than the census tracts in the city near Turner Field, but they are also somewhat larger. That being said, it still stands to reason that this part of Cobb County is well populated even if not as dense.

Household Income

There is no question about it: the new stadium is much closer to the wealthy areas of Greater Atlanta than Turner Field was, especially for those parts which are furthest north. This map shows the household income and benefit estimate range for the area. For example, a household in the lightest purple areas likely makes between $7,135 and $23,750 per year. The households in the darkest purple census tracts likely make between $154,571 and $230,763 per year. Everyone else falls somewhere in between. The wealth divide is not as stark as the racial divide, but the maps are very similar.

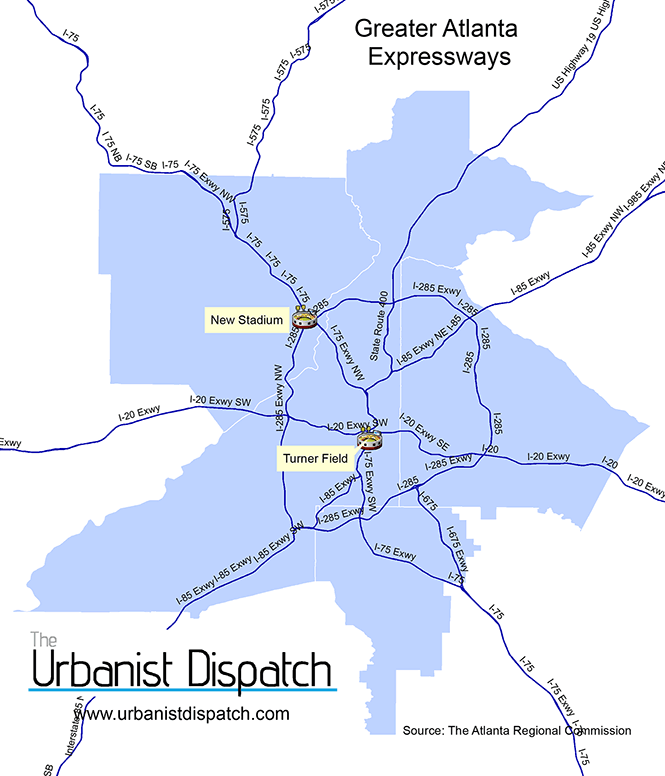

Transportation

Another map which looks very similar to the income and racial maps of the Atlanta area shows that if you live in the southern part of the city, you are much more likely to use public transit as a way to get to and from your destination. It’s no secret that Atlanta has a lot of infrastructure that is automobile focused; most of the daily commuters travel to and from work alone in their car. Where there is infrastructure for public transit, people do use it. The dark purple areas above are where the MARTA subway lines run.

We’ve established that most of the people who live near the new stadium are car owners and don’t make much use of public transit. This begs the question though – how accessible is the new stadium going to be to public transit? Or existing Turner Field for that matter?

MARTA Subway Lines

Using the train? Forget about it. Actually, forget about it in both cases. A big gripe with Turner Field is that there are no MARTA train stop at the stadium. The MARTA rail system has been around since that late 70s, however when Turner Field was planned, it wasn’t placed near a MARTA stop, and is sectioned off by highways. This means that it is going to be a very long time in the foreseeable future, if ever, that Atlanta gets a baseball stadium you can reach via train. The closest MARTA stop to existing turner field is only a few blocks away, but the highways mean it’s not an easy task, while the new stadium will be miles away from a train stop.

The bus however, tells a different story. MARTA consists of two Bus Rapid Transit lines and over 130 bus lines that blanket the metro area. The Braves also have a shuttle that you can access from the five-points MARTA train stop that will take you to the stadium in 15 minutes.

The new stadium will be accessible via bus, but it looks like a hot mess to get to. Unless you have the option of taking a single bus up, it simply does not look like an attractive option to get to a baseball game. Will new Braves shuttles take people from downtown to Cobb County? That is yet to be seen.

The best way to get to the game will be via, you guessed it, a car.

The new stadium is 12 miles right up interstate 75 from Turner Field with the I-285 circle making it easy for people to hop right on – no matter what part of the area they are from – as long as they want to drive. This will most likely remain the easiest option for those looking to see a baseball game in Atlanta.

Suburban New Urbanism

I admit, I was very skeptical of the article in the New York Times that hailed the stadium move as a boost for regionalism as well as for mixed-use new urbanist structures. I have never been to Atlanta, only driven through, but I thought “hey – who knows. There might be something here.” I took to Google Street View in order to do a virtual drive around the area where the new stadium, to see if I could get a feel for the area since I’m not there in person. After seeing places like here and here, I was left very unimpressed. I started having visions of the disastrous Pontiac Silverdome project in Michigan, where a stadium would be flanked by two major highways and an oasis of parking.

The times wrote that:

The Cobb County site is actually more in line with a new ethos of urbanism that rewards smaller, walkable communities, said Chris Leinberger, a professor at the George Washington University School of Business.

Google Street View simply didn’t match that description at all. Pretty much every negative stereotype about suburbia that I could fathom was present. Why was Chris Leinberger singing the praises of this place? I dug deeper.

What we need to keep in mind about any big development is that it should never be about what the past looked like, but about what the future would look like. What I saw on street view was the past, and that unlike a lot of places that claim they are looking into ways to create walkability and foster downtowns, Cobb County is actually doing it.

One of the culprits behind this Suburban New Urbanism is well respected urban planner Galina Tachieva. Her name you might not recognize as much as her acclaimed book: The Sprawl Repair Manual. Tachieva’s techniques broke down barriers that made walkable communities in Cobb county illegal. These barriers included antiquated regulations with overly-generous minimal parking requirements that left a lot of unused parking spaces and setback laws that meant you couldn’t put a building right up next to the sidewalk. These changes helped bring Cobb County’s form based codes and zoning laws into the 21st century. These new codes will dictate how a building should be built, not necessarily what will be inside of it, unlike zoning which separates everything based on land use. With a vision and seemingly the money to make it happen, the new stadium is planned to produce a mixed use facility that will be directly in line with what the future of Cobb County is to become. Despite being out of downtown, it’s going to be more walkable and in a better overall aesthetic than the current situation.

What to make of it all

The unfortunate reality is that while moving a stadium out of a downtown’s core looks very unappealing, the old stadium situation was very unappealing as well. Despite being downtown, it is difficult to get to between lack of public transit options and highway congestion that comes hand in hand with game traffic. The stadium is also in need of serious repairs, over $150 million worth. The city is simply going to demolish the building once The Braves have moved on. It’s very easy to dismiss the stadium project as simply politics as usual, with the convenience going to the people who have money. But as far as projects where the stadium moves outside the city limits goes, this has to be one of the most promising scenarios this country has ever seen.

That’s not to say the project is perfect, or even the most shining example. The better option, many would say, is to take all of these walkable form-based code concepts and apply them to a stadium in downtown Atlanta, where some argue that the natural form of density makes it easier to have a walkable development. Perhaps somewhere close to a MARTA train and in a place where instead of being a hidden away eyesore, it can be an anchor to revitalize a downtown neighborhood.

It could be done better. It always can be done better. While the hope is that this will be a more cohesive area with walkable streets, we simply do not know what the end result is going to be yet. It’s easy to roll our eyes at suburban stadium development, but this one has the potential to be much more than meets the eye. How much more, we’ll have to see.